A few months ago, we posted an article about salsa, dance therapy, and PTSD. The post led us to connect with one of the readers who commented on the article, Mark Word. Mark is a therapist who worked for many years as a social work officer in the Army. Today, he continues his practice as a civilian working for the military, taking a special interest in those who suffer from PTSD.

A long-time dancer, Mark also writes the blog Tango Therapist, and I wanted to chat with him about his work as a dance therapist. How did he become involved? And how can dance help those suffering from PTSD?

MO: When did you first begin dancing?

MW: After a terrible break-up with my partner while I was in a graduate program at Boston University, I first started dancing. I took a ballroom dance class, and started going to swing dance parties. It was the first real joy during that time in my life. But it was not until 2004 that I started dancing regularly. At that time it was salsa. A few years later I started tango, and now that is my favorite dance.

MO: How did you first get introduced to dance therapy and what is your current involvement?

MW: I was being trained in a type of therapy that used “bilateral stimulation” (most often left-right eye movements). Bi-lateral stimulation allows a patient to quickly recover from past traumatic events in the patient’s life. I started to realize how this same bilateral stimulation that happens during dance had the same effect of helping people get over their haunting, critical events. By 2009, I was experiencing results of this phenomenon.

MO: Your blog is Tango-Therapist.Blogspot.com. Is there a particular reason you honed in on tango dancing in particular as being therapeutic?

MW: Tango has been shown to be great for helping those with Parkinson’s Disease, and I think I know why. In tango, there is no particular “step” as with other dances. Tango dancers do not have to dance “forward-side-together-back-side-together” or even to the pulse of the music. One can dance to the melody or the rhythm or even the harmony.

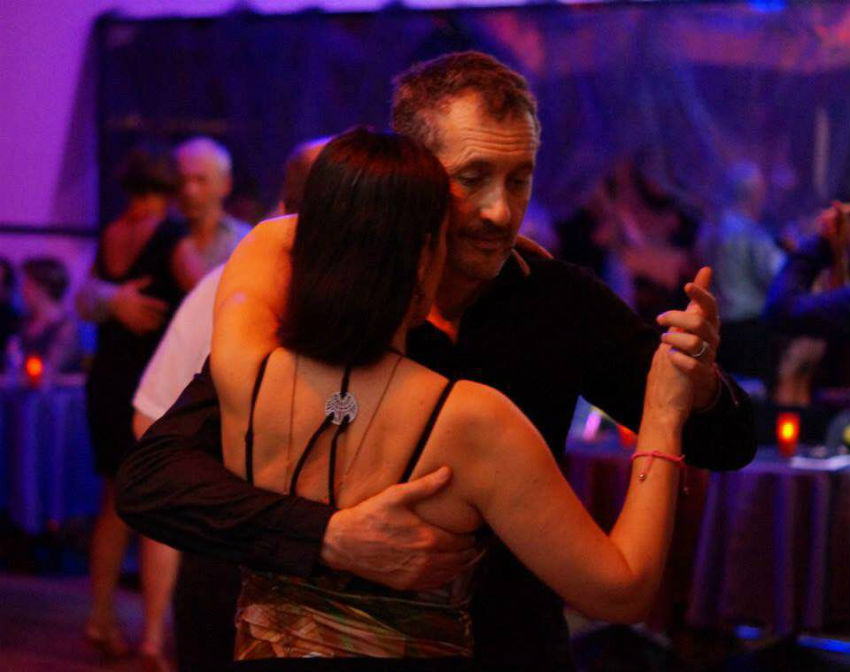

Through working with Tango, I developed the concept of the essential Three M’s: Music, Movement and eMbrace. First, I encourage trauma patients to let the music lead them. The second M, movement, speaks to the importance of movement for a patient.

eMbrace — the last M — allows them to feel supported and as if they are not alone. PTSD is a disorder of feeling separated from everyone and everything you hold dear; so the embrace is very healing. I do NOT embrace that person, but guide the patient with a spouse or partner.

So in answer to your question, here’s why tango is the best: all elements of the Three Ms are powerful by themselves. Put them together and you have a powerful synergy helping the patient get over the traumatic event.

MO: In your article “The Eight Elements of Movement, Part II:Psychological Well-Being,” you talk about the importance of grace for healing. You point out that gracefulness is both a survival mechanism and a tool for balancing psychological well-being. Can you talk about how dance therapy works in practice to utilize these concepts?

MW: Homo sapiens, as the thinking animals, really need music and dance. We think too much. Music and dance keep our psychological well-being strong and resilient. In a stressful world, moving to music is a way of finding resiliency. But what happens when we truly dance? We are not just exercising to music, or walking to music but truly dancing. This is powerful.

In dance therapy, we do yet another important thing: stop avoiding. Dance and music can be an escape, but in trauma therapy we must focus and guide the person “through the valley of the shadow of death” until they “fear no evil.” (Psalms 23)

MO: What would a tango therapy plan look like for an individual?

MW: This is complicated, but briefly stated, I would want to get an inventory of critical events in a person’s life, and measure each for the distress it causes a person to think about this event. I also would need to know what they tell themselves about the event, such as, “I should have been the one who died in combat.” I would want to know what they intellectually know to be fair, such as: “My friend would have wanted me to go on with my life.”

Then, after teaching some basics about the Three Ms, we would take that person down the dance floor for about 30 feet before asking what came up for that person while thinking about the event. There should be not too much talk. We would continue on with the music and a simple forward dancing walk. Normally, the event starts changing into a story they remember, but it does not cause them distress to think about it.

We measure improvement based on the “subjective unit of distress” that they described at the start, and also by how the intellectual self-talk now feels. If it feels real to them and no longer just what the intellectually would tell themselves, then real progress has been made.

MO: What sorts of challenges do you face in introducing someone to dance and working with them on self-expression?

MW: Well, patients often say they have two left feet or cannot dance at all. So that must be overcome before we even start. Believe it or not, this is rather easy if one understands the power of dance and that a little child is in each of us just wanting to be let out to dance!

MO: Can you think of any specific examples of dance therapy being particularly impactful or manifesting in a unique way for an individual?

MW: The easiest example is my wife, who has given permission to share her experience with your readers. When I first met her she wanted to know about tango therapy. I wanted to start by establishing some safety before going on to talk about a more tragic event in life, so I asked her to name a safe place in her life. She chose her book nook.

As one dances in one’s safe place as a guided meditation, this established safe place becomes very vivid and wonderfully present to the dancer. But in her case, her throat became constricted. I knew exactly what happened. Since I did not know her trauma history, I figured that her book nook was tied to some critical event in her life.

I quickly found out what had happened. She had once gone to her book nook to get away from her physically and emotionally abusive mother, often going there after critical events. So with her permission, we went into the trauma therapy using the Three Ms until she was free. I forgotten all about doing this with her. But later, I overheard her telling a friend that now when she goes home to visit, her mother cannot upset her with any unkind statement now. Suddenly they had a much better relationship, and that has not changed since that one treatment.

I have had limited freedom to use tango therapy within the military, but for a short time, I had a supervisor who gave me permission to use tango therapy with a couple. The soldier had PTSD from sexual abuse, as well as survivor’s guilt from combat. His homicidal feeling towards his abuser dissipated in less than 20 minutes, and then later, his combat PTSD dissipated in a separate session. I was baffled by how fast it went. In sharing this with another therapist, she went to my supervisor and complained that I could not use methods not approved at much higher levels. So I stopped trying. It is my great hope to begin this work when I retire from the Federal system.

MO: What would you say to someone who wants to try dance therapy?

MW: I would want to caution people who might think that dance is automatically therapeutic. It can be if it is isolated to dancing in a safe environment and with safe people. Going out to a bar and dancing would seem to also be great, but it could — and probably will — make things worse for someone suffering from PTSD. Dance therapists are being trained in every metropolitan center in the US and Europe, and I would recommend finding someone who has practice in the field if you want to try it.

You can read more about Mark Word’s thoughts and experiences related to dance therapy on his blog.

Leave A Reply